The current NZ Government recommendations for youth participating in physical activity are pretty simple; they boil down to ‘Sit less, move more and sleep well’ (Ministry of Health, 2017). However, as a PT you need to be able to understand the mechanisms for safely training youth, how to teach them functional movement skills, and how to progress their components of fitness when applicable.

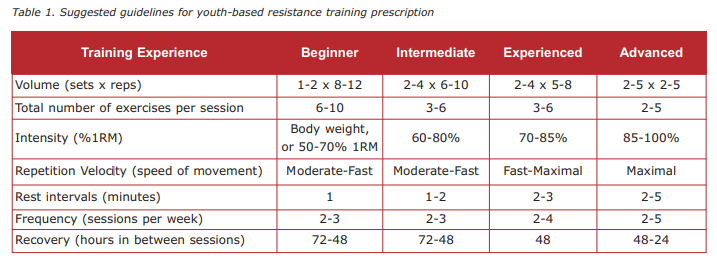

So, how do we know how to set the appropriate training for young people, and what are the current recommendations? This article will cover the current recommendations, training specific to physical maturity, and components of fitness, plus some great reference articles for further reading.

As you might have previously read on our learning platform, participating in exercise and physical activity provides a range of benefits to children (aged from 2 years to the onset of puberty) and adolescents (aged from puberty to 18 years). These benefits can relate to improved strength, speed, and endurance; improved motor patterns and coordination; reduced risk of sports-related or overuse injuries by up to 50% due to strengthening ligaments, tendons, bone and muscle; and establishing lifelong positive habits and benefits related to participating in regular physical activity (Lloyd et al., 2012).

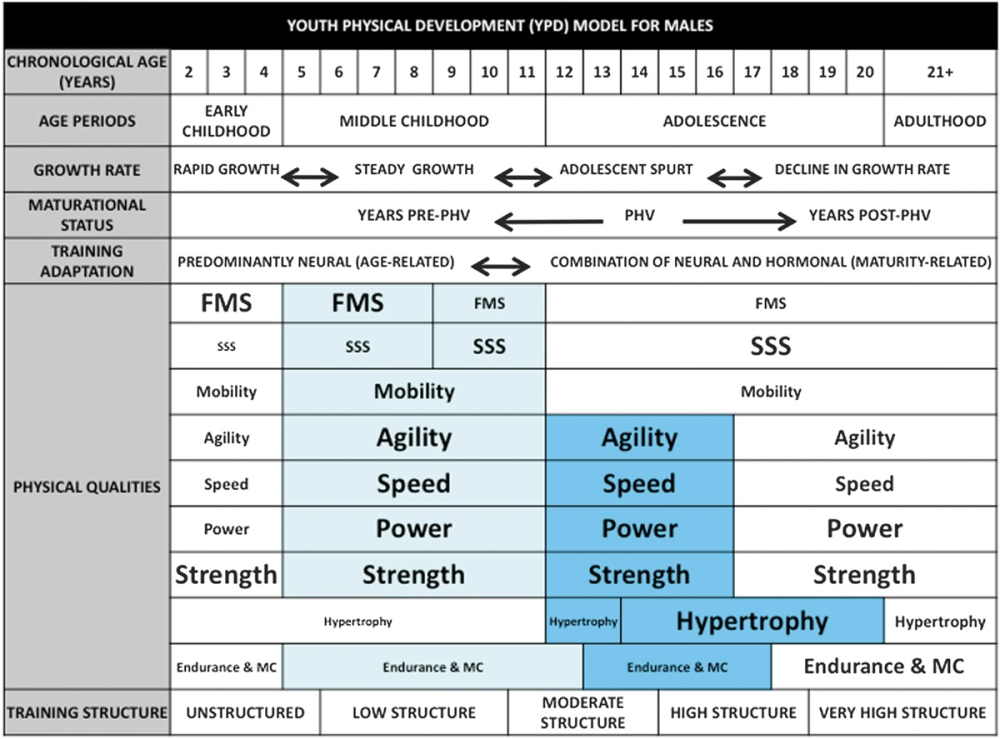

The age and the current movement ability of each young person will have an impact on the type and level of training you should perform. The first thing you want to understand is that functional movement skills (FMS) - such as running, jumping, kicking, throwing and balancing - are very important as children grow up. These basic movement patterns help to prepare them for more complex motor pattern movements and sport-specific skills as they age.